What Happens if the Election is Unresolved?

courtesy of the New York Times

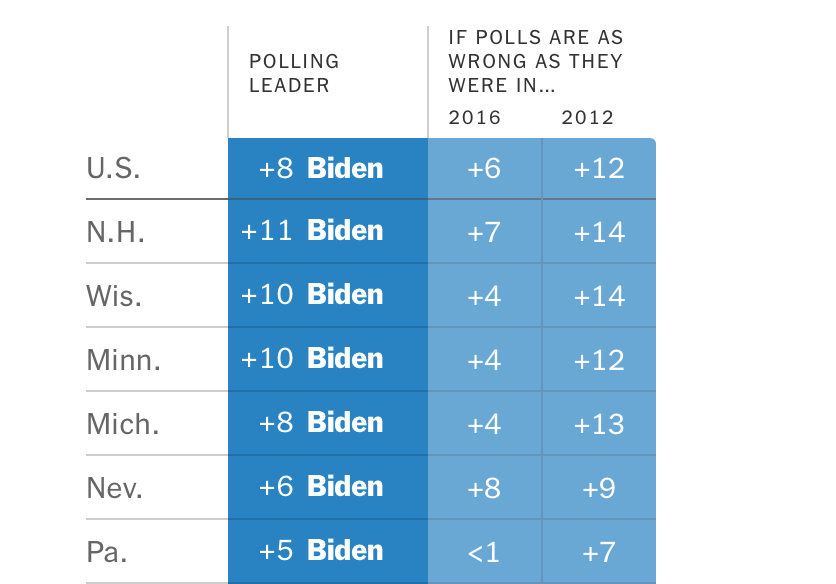

Poll from the New York Times showing Biden leading nationally and within 6 key states, with a comparison to the margin of error in 2016.

November 3, 2020

November 3, 2020. The beginning of the end of a high stakes election year with incumbent Donald Trump representing the Conservative party and former Vice President Joe Biden the face of the Democrats. According to the New York Times no matter the method of polling Biden is leading, mostly outside of the margin of error. Of course, as seen in 2016, the polls can be wrong. The Trump presidency has put America through numerous unorthodox situations, leading many to fear the constitutional battle that could arise if, in the event of a Biden victory, Trump refuses to concede.

Trump’s attorneys have fabricated a groundwork to undermine results that don’t cast him as victor. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, in discussing Trump’s willingness, or lack thereof, to leave office, an anonymous advisor from the Trump Administration warned, “I think November could be a really bad month for this country.” The administration has denied allegations of a strategy that would cite vote irregularities in many states including key battleground states like Arizona; however, the legal team has said they will scout every opportunity to ensure the President’s reelection. In an interview with Axios, Trump himself admitted that he will not commit to a peaceful transition, especially with the widespread implementation of mail-in ballots.

Trump’s incendiary statements suggesting that he will take the election by force are worrying even Pentagon officials. Concern increased notably after a statement at a rally earlier in the year saying he would garrison a major show of force from law enforcement on election day in what he detailed as a national poll-watching effort. Such actions of voter suppression are illegal.

It is disquietingly difficult to say what would happen if the election remains contested for any reason. If the final count awards Biden victory on a small margin there is a high plausibility Trump will choose to contest this, in which case American Election Law lays out very few and unsettlingly vague guidelines. The vote could go to the house with each delegate casting one vote that would determine the President while the same plays out in the Senate for the appointment of the Vice President. The more likely scenario, however, is that decisions within states will rest on partisan majorities, where each state will declare a victor for themselves and whoever is chosen by a majority of states is the winner. In states like North Carolina, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin where the Legislature is Republican but the Governor is Democratic the legislature will likely certify Trump’s electors and the Governor certify Biden’s thus both candidates will have the opportunity to declare false victory in these states. This would result in the false allocation of votes and erroneous declarations of victory.

Similar contested elections have occurred only twice in American history. Once in 2000 with Bush v. Gore which ended in December championing Bush, and in 1876 with Tilden-Hayes, in which Hayes was not identified as president-elect until two days before the inauguration.

The twentieth amendment, ratified in 1933, sought to eliminate any future recurrence by designating that the president’s term ends at noon on January 20, however, it does not provide legal guidance in a scenario where both candidates are declaring victory and potentially performing inaugurations at the same time. The amendment does specify that if there is no president-elect to take over at noon on January 20th the acting president would be the speaker of the house. This, however, is only applicable if there is no president-elect, so what happens if there are two?

After the electors have met and voted in each state, under the twelfth amendment they are mandated to send their Electoral College votes to the president of the senate who at this point is still the incumbent vice president of the United States. An issue with this is that within each state Biden electors and Trump electors might hold separate meetings on the same day and send in separate decisions just as the electors did during the Tilden-Hayes election. The twelfth amendment instructs that after the electors have sent in their submissions there is to be a special joint session of Congress on January 6th. In this session, the President of the Senate is to open the certificates containing electoral votes, and as said in the amendment “the votes shall then be counted.”

Note the use of passive voice in the above quote. Who specifically is tasked with counting the votes? Is there an outside party who does so, all of Congress, the president of the senate? The wording is dangerously ambiguous if Congress is to strongly dispute the counting of the votes. There is no tiebreaker in the constitution if Congress were to polarize with the house electing one candidate and the senate the other.

In 1887 the Electoral Count Act, which even in the time of its ratification was considered borderline unintelligible, was instituted. Under one interpretation it essentially says that if Congress were to receive more than one electoral submission from a state on January 6 and the senate and the house were to disagree on which one was valid, the electoral votes would go to the electors who were endorsed by the state’s governor. However, because of the convoluted phrasing, other interpretations leave the responsibility of deciding on the shoulders of the president of the senate. In the 2020 election that would task Vice President Mike Pence with deciding whether he and Trump were reelected. Needless to say, this would result in a biased decision. The legal reasoning behind this Act is lost on modern-day political scientists and would be undoubtedly disastrous for legitimately electing a president.

If the latter scenario were to play out Speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi would likely assert that the former be adopted instead.

The 1887 statute says that the electoral votes of the next state (alphabetically) can not be counted until the previous dispute is settled and votes are given to one candidate. So in the event that a deadlock between the house and the senate occurs, speaker Pelosi could proclaim the electoral counting, and consequently, the election itself is incomplete unless the senate president accepts the submissions from the governor backed electors. Mike Pence is only senate president until his vice-presidential term is up on January 20, thus if the disputes are stretched through that date Speaker Pelosi would become “senate president-pro-tempore,” so she could carry out the acceptions of the electoral college votes based on the governor’s stance. However, Pence could also highlight a section of the statute that gives him the power to preserve order thus moving the proceedings swiftly to be completed by inauguration day.

The antithetical powers granted from this statute could yield an inauguration day where Mike Pence declares victory for him and Trump, but Pelosi insists there is still no president-elect.

If such a deadlock between the house and senate were to transpire it is likely that the country would be rioting with massive demonstrations advocating for either party or against the system as a whole. If inauguration day were to come around with no clear-cut answer, as civilian chaos ensues the Supreme Court could decide the election. With the confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett on October, 25 the court now sits comfortably to the right with a 6-3 majority and would almost certainly side with Trump. However, it would be more constitutionally moral for the court to forfeit this right on the grounds that the election consists too much of a political nature and is beyond judicial power, just as they did in 2000 with Bush v, Gore.

This still leaves the country wondering who their president is though. In the event that the Supreme Court denies involvement in the decision the prevalent question will be, is the Commander in Chief reelected president Trump or Acting President Pelosi? There is no constitutional answer.

In order to avoid such a deadlock crisis, early action across the country was pivotal. Senator Marco Rubio R-FL proposed that states be given three and a half weeks extra to count their popular vote and preemptively dissolve any disputes. He even introduced a bill that extended the deadline for certifying electors, the federal “safe harbor” deadline, from December 8 to January 1. The Atlantic has highlighted their support for a bipartisan committee, preferably selected by Congress, that would be tasked with persuasively guiding the divided Congress, whether this truly assisted in decision making or just alleviated stress and anxiety.

The message we can pull from this and the 2000 election is that the American electorate system is not sturdy or resilient enough to handle elections within the margin of error or subject to thorough disputes and legal battles. If the inauguration day comes and the election remains irresolute, American democracy may not be able to withstand the torrent of nationwide chaos, thus the importance of voting is exacerbated for each and every US citizen.

Penny S Voyles • Nov 6, 2020 at 5:27 PM

Great article and amazing research. Maddie is quite a constitutional scholar, congratulations on a job well done. Let’s hope we don’t have to resort to all of the legal challenges and the country will have a President Elect very soon so we can move on to heal this divided nation.